- Home

- Gerrick D. Kennedy

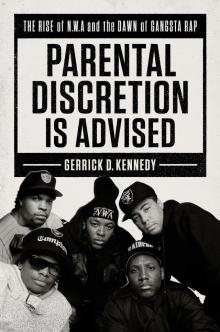

Parental Discretion Is Advised

Parental Discretion Is Advised Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Jermaine, Charles, and Robert. I am, because of you.

PROLOGUE

SEPTEMBER 07, 2013 * SAN BERNARDINO, CALIFORNIA

A maze of metal barricades was stuffed with hundreds of rap fans waiting to file into San Manuel Amphitheater. Inside, heavy, pounding bass from the DJ’s turntable drowned out the piercing beeps of metal detectors that greeted early arrivers. It was opening day of Rock the Bells, an annual hip-hop festival that was launched in Southern California and toured throughout the world during its decade run. Twenty thousand fans made the pilgrimage to the hills of the Inland Empire desert, roughly an hour and a half outside of Los Angeles, for two days of music performances. The mix of underground genre outliers; revered elder statesmen; and young, chart-topping wunderkinds allowed Rock the Bells to enjoy a status as the preeminent destination for hip-hop fans well before massive music gatherings like Coachella, Bonnaroo, and Lollapalooza diversified their lineups to reflect rap’s surging mainstream dominance. A gust of wind swept dust through the security line as workers confiscated prohibited paraphernalia from disappointed fans who unsuccessfully hid marijuana blunts or glass one-hitters they hoped to bring into the festival. It was well over 100 degrees on this Saturday afternoon, but more palpable than the triple-digit temperature was the anticipation from fans waiting to get inside.

The bill was a heady, extensive representation of several generations of hip-hop acts that traversed mainstream and alternative lanes of the genre. Common; Jurassic 5; Kid Cudi; Pusha T; KRS-One; Talib Kweli; Kendrick Lamar; Tech N9ne; Earl Sweatshirt; Slick Rick; Juicy J; Too Short; Immortal Technique; E-40; Tyler, the Creator; Doug E. Fresh; Lecrae; J. Cole; Rakim; A$AP Rocky; Danny Brown; the Internet; and Wu-Tang Clan were all booked for a weekend that marked the landmark tenth anniversary of the festival.

Also on the marquee was Eazy-E, the “Godfather of Gangsta rap” and founder of the most notorious hip-hop group of all time, N.W.A.

Nearly two decades had passed since Eazy took his last breath, losing his battle with AIDS years after N.W.A crumbled amid accusations of shady contracts and bitter rivalries. Eazy was long expunged from the narrative of hip-hop, succumbing to the mores of irrelevance after his hard-core image morphed into a sort of zany caricature of itself. But today he would rap again.

In the months leading up to the festival, Rezin8, a San Diego–based company that specializes in immersive design, was hard at work resurrecting Eazy. A combination of green-screen motion capture, animation, multimedia, and Eazy’s children’s memories produced what was hyped as an “accurate, authentic reflection” of the rapper. Eric “Lil Eazy-E” Wright Jr. was used for the avatar’s body. Derrek “E3” Wright provided the voice. And Eazy’s “face” was constructed using an imprint of his daughter, Ebie Wright.

“You’re not going to be looking at 1987 Eazy-E, you’re going to be looking at 1994 heyday,” Eazy-E’s widow, Tomica Woods-Wright, said ahead of the festival. “You’re going to get probably what most people remember of that last impression of that era he was in.”

“We aren’t trying to mimic something, you’re creating something,” Wright continued. “We’re building, in the capacity, a reflection to carry on that’s a piece of him. It’s not going to be him, but it’s going to be as damn close as you can get.”

On what would have been Eazy’s fiftieth birthday, the technology that brought Tupac Shakur, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, and Michael Jackson back from the dead for another musical thrill introduced Eazy’s digitized likeness for a “virtual performance” (as it was billed by the festival organizers).

A dozen incandescent bulbs cast a blue glow over the stage as plumes of dank marijuana smoke hung over the audience. Despite years of beef among the group, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, the Cleveland rap posse Eazy signed to his Ruthless Records, reunited for the occasion and had just performed a set of its biggest hits when the lights came to a slow dim. From the amphitheater’s rafters, a complex rig descended slowly as multiple smoke machines sent thick clouds of fog, pale red from a strip of lights, rolling across the stage. With the push of a button, there he was again, clad in his signature slate-gray Dickies that sagged slightly and a black hat with “Compton” stitched in white, Old English–font letters.

Eazy—or, more accurately, the digital composition of him—stood still, soaking up the rapturous applause from the crowd.

“We Want Eazy! We Want Eazy! We Want Eazy!” the crowd cheered.

When his former bandmate DJ Yella, behind a pair of turntables, cued up a beat as startling as an air-raid siren, Eazy started bobbing his head to the music and finding his swagger before addressing the crowd, many of whom hoisted smartphones in the air to record the moment. There were even gasps of disbelief as one of rap’s earliest fallen heroes was resurrected.

“What’s up, LA! Make some motherfucking noise,” digital Eazy shouted.

Satisfied with the love he was receiving, Eazy launched into the verse that caps one of the most famous rap songs of all time, a record that transformed the genre forever.

“. . . Straight outta Compton is a brotha that’ll smother yo’ mother,” Eazy rapped amid the shrills of twenty thousand rap heads. An overwhelming number of Compton hats and T-shirts emblazoned with “N.W.A” in eerie red letters—or ones with the faces of its members in mug shot–like poses—could be seen in the audience. Throughout the weekend, Eazy’s face was omnipresent, as scores of savvy street vendors camping out in the parking lot sold an array of homemade N.W.A paraphernalia for well below what merchants inside charged. Eazy would have appreciated the hustle.

“Dangerous motherfucker raises hell, and if I ever get caught I make bail,” Eazy continued as his holographic likeness bounced alongside DJ Yella without missing a beat.

Without as much as a pause, Eazy then dove into another of his indelible, hard-core tales of street life, “Boyz-n-the-Hood”—a song that transformed the former drug dealer into an unlikely rap sensation. The crowd, some of whom were not even alive during the peak of Eazy’s fame, joined in unison to chant the anthem’s most famous bars:

Cruisin’ down the street in my six-fo’

Jockin’ the bitches, slappin’ the hoes

For a moment Eazy was alive again, basking in the love that has largely evaded him since his death, as his legacy is often overlooked in the pantheon of fallen rap gods. Unlike Tupac and the Notorious B.I.G., he didn’t go out a hip-hop martyr consumed by the violent street life dominant in his lyrics. But like his life and his career, Eazy’s moment onstage was all too brief. Just as quickly as he had arrived, he vanished into a cloud of smoke. And the show went on.

COMPTON’S N THE HOUSE

Of the many big bangs that have transformed rap over the decades, N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton is one of the loudest. It was a sonic Molotov cocktail that ignited a firestorm when it debuted in the summer of 1988. Steered by Dr. Dre and DJ Yella’s dark production and Ice Cube and MC Ren’s striking rhymes, and brought to life by Eazy-E’s wicked charm, the record fused the bombastic sonics of Public Enemy’s production with vicious lyrics that were revolutionary or perverse, depending on whom you asked. The world hadn’t heard anything like it before. Radio stations and MTV refus

ed to add the title song to their playlists. Critics didn’t get it, couldn’t see past the language, or, worse, refused to acknowledge it as music. Politicians even launched attacks, working to great lengths to condemn the music and its creators. N.W.A were to hip-hop what the Sex Pistols were to rock—and really, what’s more punk than having a name that dared to be spoken or written in full, and music that incensed a nation? Red-faced and outraged Americans protested the group, police officers refused to provide security for its shows, and the FBI got involved, but that didn’t stop Straight Outta Compton, N.W.A’s debut album, from selling three million records without a radio single.

With Straight Outta Compton, N.W.A didn’t just manage to put its hood on the map, the group forced the world to pay attention to the rap sounds coming out of the West Coast. It’s an album that provided the soundtrack for agitated and restless black youth across America with its rough and raunchy tales of violent life in the inner city, expressed through razor-sharp lyrics. “It was good music,” LA rap-radio pioneer Greg Mack said. “And the lyrics, they meant something.”

The emergence of N.W.A—who billed itself as the World’s Most Dangerous Group—in the late eighties provided a jolt to the rap industry. Public Enemy had already helped redefine the genre by ushering in aggressively pro-Black raps that were intelligent, socially aware, and politically charged. But N.W.A opted for an angrier approach. The group celebrated the hedonism and violence of gangs and drugs that turned neighborhoods into war zones, capturing it in brazen language soaked in explicitness. “Street reporters” is what they called themselves, and their dispatches were raw and unhinged—no matter how ugly the stories were.

Like the Beatles, N.W.A’s lineup was stacked with all-stars: Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, and MC Ren would become platinum-selling solo rappers, while DJ Yella helped Dre break ground on a new sound in hip-hop. They were the living embodiment of the streets where they were raised, and there was zero pretense about it. And when it came to subject matter, with N.W.A, politics took a backseat. Instead, frustrations about growing up young and black on the streets of South Central Los Angeles became the driving force behind their music. Gangs, violence, poverty, and the ravishing eighties crack epidemic swept through black neighborhoods like F5 tornadoes. People were angry and restless, and without a flinch N.W.A documented its dark and grim realities like urban newsmen.

Straight Outta Compton was a flash point that spoke for a disenfranchised community and disrupted the order of those who were confronted with the voices and images of a community they’d much rather ignore. Black teens and young adults immersed in street life, yet looking for something to hold on to, flocked to the album. And so did white, suburban, middle-class teens who knew nothing about the “hood” or a life inside it, but looked to rap as an outlet for rebellion in the same way their parents gravitated toward the angsty countercultural attitudes percolating in rock music during the 1960s.

As unapologetically violent, misogynist, and problematic as their lyrics often were, the group’s harrowing depictions of urban nightmares provided a vital response to the growing disenfranchisement from the Regan-era politics that had transformed the nation and created an economic catastrophe for metropolitan Los Angeles. N.W.A introduced an antihero. The way Melvin Van Peebles’s groundbreaking 1971 film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song used America’s longstanding perception of black men as seething, violent hunks to politicize the image, N.W.A brought it to life by mixing reality with fantasy through its music—and the result was as terrifying as it was successful.

At its peak, Eazy’s Ruthless Records—a label he started strictly as a means to get off the streets—was the number-one independent label in the industry and the largest black-owned indie since Berry Gordy’s legendary Motown empire. Without Eazy laying down the foundation for hustlers-turned-record-executives, who knows if Death Row, Bad Boy, No Limit, or Cash Money could have existed. How would Jay-Z ever have known he could go from slinging crack cocaine to creating Roc-A-Fella had Eazy not done it less than a decade before?

Ice Cube once said the music took off because it was a moment in time bottled up and shaken until it burst. It’s no surprise then that the group’s most insidious track, “Fuck tha Police,” became a rallying cry in LA after a group of white police officers were acquitted in the savage beating of unarmed black motorist Rodney King. Those three words became a mantra, shouted and painted on walls by those who pilfered and torched the city in the days after the acquittal, in what remains one of the deadliest, most destructive uprisings in American history. More than a quarter of a century before the Black Lives Matter movement and a new generation of youth turned to social-media activism as a means of protest against police brutality, N.W.A were screaming “Fuck tha police.” Their lyrics were purposely confrontational. They shouted furiously to push back against racial profiling and offered insight into the daily turmoil of inner-city youth through visceral storytelling, but they just as well promoted misogyny, homophobia, and sexual violence without abandon. “We had lyrics. That’s what we used to combat all the forces that were pushing us from all angles: Whether it was money, gang-banging, crack, LAPD,” Cube said. “Everything in the world came after this group.

“N.W.A was the World’s Most Dangerous Group. We changed pop culture on all levels. Not just music. We changed it on TV. In movies. On radio. Everything. Everybody could be themselves. Before N.W.A . . . you had to pretend to be a good guy.”

N.W.A shocked middle America, scared the government, and sparked conflict with law enforcement. Although their run together was short, N.W.A’s music encouraged a generation of young, black emcees to explore their rawest thoughts, no matter how obscene or radical. Today, hip-hop is seen far differently than it was during N.W.A’s rise. Hip-hop is credited as the single most influential genre in American pop music over the last half century, as its artists have long gone from persona non grata to pop stars, corporate pitchmen, actors, fashion designers, tech moguls, and executives—and it wouldn’t have happened if a group of men from Compton and South Central didn’t light the fire.

Compton wasn’t even on a map in 1985. It wasn’t that the mostly African American suburb in South Central Los Angeles was some deserted town or a Podunk dump in the shadows of the glamorous big city, but it may as well have been, considering that an official county publication outlining the cities, towns, and neighborhoods of LA inadvertently left it off. For those that didn’t reside somewhere within its ten square miles or one of the surrounding cities touching its borders—Willowbrook, West Compton, Carson, Rancho Dominguez, Long Beach, Paramount, or Lynwood—Compton was virtually nonexistent.

And it was easy to forget about Compton amid the landscape of Los Angeles, a city that’s a literal representation of the California Dream, with its lush beaches, sunny weather, and glitzy industries. Compton is located just south of the concrete ribbons of freeway connecting downtown Los Angeles to the beaches of Santa Monica and Venice, to the entertainment capital of Hollywood, and to the opulence of Beverly Hills. Its geographic centrality to Los Angeles County gave it the name “Hub City.” In the mid-1980s, Compton, then a city of nearly 90,000 residents, looked much like any other suburb. Wooden bungalows painted a multitude of colors with porches and sprawling yards lined streets dotted with towering palms and banana trees. During that time, middle-class black and brown families in Compton were hard at work toward their own version of the California Dream.

That’s what Richard and Kathie Wright were in search of when they made the move to Compton from Greenville, Mississippi, during the Great Migration. The Wrights settled into a simple, traditional middle-class way of life. Kathie taught grade school and Richard became a postal worker. Unlike LA, however, life in Compton—and throughout South Central—was far from the glamorous way TV shows and films depicted. South Central communities struggled to rebound from the 1965 riots in Watts, which left a vital strip of the neighborhood’s business district blackened to the point that it was rechriste

ned “Charcoal Alley.” President Richard Nixon’s Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, a public program created to provide desperately needed jobs, helped South Central residents bounce back from the recession of the early 1970s. But when President Ronald Reagan moved into the White House in 1981 he nixed the initiative. By 1982, one year into Reagan’s first term, South Central was in crisis. Unemployment and poverty tested families. Startling high school dropout rates drove up crime. Yet, more ominous elements were at play, as an epidemic of gangs and drugs started to ravish communities.

“If you sat on this porch at night and just listened real hard, you’d hear nothing but gunfire,” Ice Cube said of his parents’ South Central abode. “I’ve heard it so much in my neighborhood that I can’t hear it no more. At night, you’ll see the helicopter flying around here with the spotlight on, looking for somebody. If you hear a car with a beatbox booming at night, you know they’re out looking for somebody. As long as you can’t see where they’re coming from, gunshots aren’t scary. Now, if you see the fire from the gun, then you run . . .”

A dangerous mentality set in among Compton youth: “I grew up in the hood, I’m going to die in the hood.” It was understandable. Jobs were hard to come by and people were just trying to survive.

The hope and promise felt by a generation of black migrants was replaced with despair and disillusion in their offspring. An area that was once a beacon of black middle-class achievement had become one of blight by the 1980s. Young black men in Los Angeles were six times as likely to be killed as their white peers, and Compton had a murder rate that was more than three times the per-capita rate of LA—a city of little more than three million people. “It was a dangerous time. Everybody was trying to get their hustle on. If you encroached on somebody else’s territory, there’s problems,” remembered Vince Edwards, who grew up in Compton and goes by CPO Boss Hogg. “The gang culture was prevalent. You had all these dealers trying to get their money made so you had to worry about them—and you had to worry about crossing gang territory.”

Parental Discretion Is Advised

Parental Discretion Is Advised